Like pretty much every other DC film franchise, the Christmas release of the much anticipated “Wonder Woman 1984” has left social media fractured on whether or not the film is good, bad, or unwatchable. While its critics point out the problematic (and downright creepy) nature of Steve Trevor’s “reincarnation,” its fans praise both the film’s actors and its light-hearted spirit, comparing its upbeat optimism to that of Lynda Carter’s classic show.

Because of the subjective nature of storytelling, pretending like there is only one true lens to look at a film is pretty naïve. But while I find most of the criticisms of WW84 valid, one particular gripe that keeps popping up on social media that is bothersome on a deep level is the claim that the film lacked diversity with its ‘all White’ cast.

The reason this particular critique can be irksome to many LatinX nerds like myself is that WW84’s lead villain, Max Lord, is not only played by one of the most beloved Latino actors currently working in television, but that the film actually goes out of its way to highlight his character as a poor Latino immigrant struggling with identity issues during a time in America where diversity in media was all but nonexistent. He is a man who grew up without privilege, and thus became obsessed with it as an adult. He very much represents real-life LatinX celebrities and politicians who build facades around ‘Whiteness’ in order to better navigate in a society that either entirely ignores brown people or goes out of its way to crush their spirits.

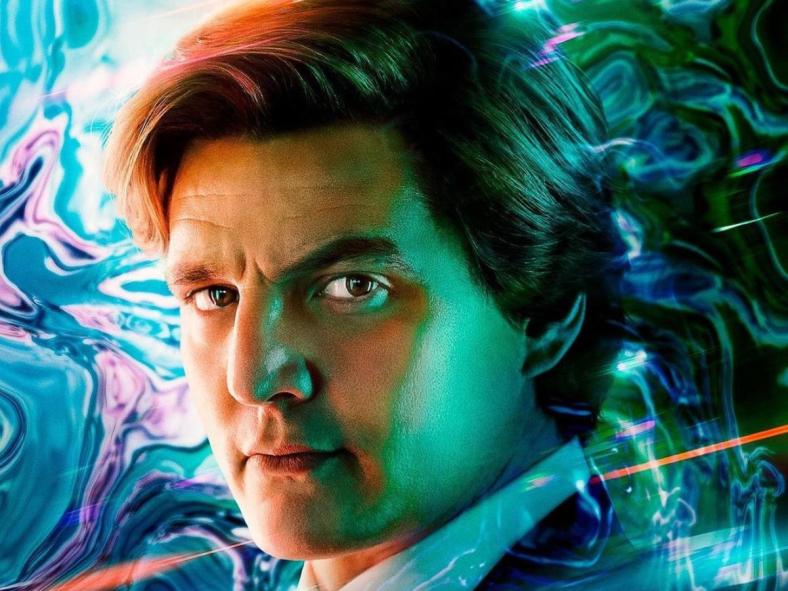

While the character of Max Lord in the comics is explicitly white, director Patty Jenkins picked Chilean actor Pedro Pascal to tackle the villainous role in her 80s-infused film. Pascal, who is known for playing morally gray characters such as Oberyn Martell on “Game of Thrones” and Din Djarin on “The Mandalorian,” is wonderful at injecting his characters with a complicated edge that makes them relatable to viewers.

Whether it’s the Prince of Vipers or a faceless mercenary, Pascal’s characters are enchanting anti-heroes. But upon seeing promotional material for Max Lord, I quickly became skeptical over whether or not I would enjoy his performance. His appearance resembled that of a living Ken doll, and gave me flashbacks to other films that “bleached” their LatinX actors in order to make them pass as White characters.

Though I find nothing inherently wrong with Latinos portraying White characters, when White is the *only* ethnicity they are allowed to portray, their visibility in television and film becomes increasingly insignificant.

However upon watching WW84, it was clear that Pascal wasn’t actually playing a White guy – he was playing a poor Latino *pretending* to be a rich White guy. His version of Max Lord was entirely different than his comic book counterpart. In fact, Max Lord isn’t even his real name; it’s Maxwell Lorenzano. The film first introduces Pascal’s character as an over-the-top 80s TV personality loudly proclaiming catchphrases like “Life is good, but it can be better!” and “If you can dream it, you can have it!” across the airways.

His bleached hair, “glowing” biotin-soaked skin, and over-enunciated gameshow host accent all gives off “Wolf of Wallstreet” vibes. His failing company, Black Gold Cooperative, has devolved into a giant Ponzi scheme thanks to a run of bad luck and poor business decisions, leaving him with nothing, but his hallow, almost Trump-like ‘brand.’ His entire persona is built off one big lie, making him the antithesis of Wonder Woman, who is the goddess of Truth.

But as the film progresses, we start to understand why Lorenzano built an entire image around the ‘sleazy White guy’ archetype. As it turns out, Maxwell had a very hard life growing up, one that involved extreme poverty, an abusive father, and endless racism from his White peers.

During a flashback montage, Max is shown as a young immigrant boy being relentlessly teased by his classmates with such gems as “He doesn’t even speak English!” and “Eww, what is he eating?!” and “Look at his shoes!” As he gets older, we see Max enviously looking upon all the wealthy White students walking out of a university he’ll never be able to attend simply because it’s outside his economic means. Though he tries to rise above his station in life, it’s clear the system is rigged against people like him – a lowlife, as his miserly White business partner labels him. So to become successful, Maxwell Lorenzano became Max Lord, the epitome of the White alpha male circa 1984.

When his character first crosses paths with the film’s hero Diana Prince (Gal Gadot), Pascal delivers a manic, overly friendly performance that has an odd, uncanny valley presence to it. His demeanor immediately sets off red flags for Diana, though it enchants her coworker Barbara Minerva (Kristen Wiig). It is in this scene alone where Max hints at his ethnic heritage, responding to Minerva’s awkward flirting with “You like Latin dancing?” while playfully shaking his body.

The only real part of Max that can’t be bleached into a façade is his young son, Alistair (Lucian Perez). Unlike his father, Alistair cannot pass as White by any stretch of the imagination, and Max knows it. His love for his son is apparent, as is Max’s fear that he’ll grow up feeling ashamed of where he came from. To make the world a better place for both himself and Alistair, Max “dreams big.”

The crux of the film revolves around a magical MacGuffin, the Dreamstone; – a 4,000-year-old artifact that shows up throughout human history. Last appearing during the fall of the great Mayan Empire, the Dreamstone is an artifact imbued with the power of a malevolent god named Dechalafrea Ero. The stone acts as an “evil genie,” granting its user one wish, but taking something in return. Though the Monkey’s Paw trope has been used to death in pop culture, WW84 takes it in a unique direction by having Max wish to be the Dreamstone itself, giving him the ability to grant wishes while magically appropriating something in return. It’s a rather unorthodox wish, given that basically anything in the cosmos is on the table.

But Max doesn’t want physical power like his villainous counterpart Cheetah; he wants systemic power. As in the very thing he had always been denied in life. He doesn’t want to simply be the man who receives the million dollar checks; he wants to be the man who writes them. It is unclear exactly how Max first learns about the Dreamstone, but it’s vaguely implied that when his money situation got desperate, Max looked inward towards his Indigenous roots for a miracle. That miracle, unfortunately, was a being that possibly killed his ancestors. Though the nationality of Pascal’s character is never mentioned, that he’s willing to make a deal with an entity responsible for destroying a pre-Columbian society in exchange for power is a rather damning metaphor regardless.

Though his actions come off as erratic, everything Max does after becoming the Dreamstone made sense to me. He seizes the stocks to his now booming company, flies to Cairo to steal the oil rights from competitors, snatches up the congregation of a famous televangelist, and is granted full political immunity and tax exemption from Ronald Reagan, all while offering something in return. His final villainous act is to take over a top-secret Global Broadcast Satellite, allowing him to take over television sets across the world via particle beam technology.

Simply put, Max Lord becomes the god of Media. When all is said and done, Max has taken over every systemic institution in the world. He goes from being crushed by the system to becoming the system itself, at the cost of destabilizing world governments and hurling the planet into apocalyptic World War.

His actions are maniacally selfish, but it’s important to remember that the Dreamstone steals something in exchange for its gifts, and from Max Lord it stole his heroic intent. Whatever good Max had hoped would come from controlling the levers of power vanished not long after being granted magical abilities. At the heart of Pascal’s character is a Latino immigrant who became so obsessed with assimilating to American society that he becomes wholly consumed by it. The ‘greed is good’ mantra of 1980s capitalism becomes all he understands, and when Wonder Woman demands he set the world right by renouncing his ill-gotten power, Max laughingly retorts “Why would I, when it’s finally my turn?”

Why is this villainous character so important to me?

Because he reminds me of my younger self, during a time when renouncing my Mexican heritage felt like the only way to not be invisible. From my years as a teenager and well into young adulthood, I too bleached my hair, wore blue contact lenses, put on sunblock religiously, and refused to learn Spanish from my family all in an attempt to create a persona of Whiteness. Growing up, I would hear stories from my grandmother about teachers who used to beat her for speaking Spanish in public, and of America’s racist history towards Latinos as a whole; a history that American pop culture goes out of its way to ignore.

I felt like I wasn’t allowed to be a proud Latino in the 90s, partly because I am multi-ethnic, but mostly because I felt like being Mexican-American was just too hard. As a small child I’d watch as random men would racially-fetishize my mother in public spaces. I’d listen to the parents of my White friends proclaim, “Mexicans were stealing jobs.” I’d get teased anytime I did “something ethnic.” It became so exhausting that I leaned into a false narrative I created for myself.

I didn’t see many authentic representations of Latinos growing up, so like Max, I based my persona on the ‘douchebag’ White guys I saw on television. Chairman of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, Joaquin Castro, once wrote in an oped for Variety that “Latinos Love Hollywood, but Hollywood Hates Latinos.” Citing a study by the USC Anneberg Inclusion Initiative, Castro pointed out that Latinos only represent 5% of speaking roles in film, 4% of working directors, and 3% of producers. Conversely, Latinos also represent nearly 50% of the population of Los Angeles.

This insanely disproportionate lack of representation has created a false narrative about Hispanic, LatinX, and Indigenous people throughout media for generations. And it’s that feeling of invisibility that creates someone like Max Lord, a self-hating conman who capitalizes on privilege he doesn’t even have.

In 1984, it would have been very hard for someone of Maxwell Lorenzano’s ‘lowlife’ background to earn a top TV spot, but America would gladly give airtime to a Gordon Gekko clone like Max Lord. But unlike his White doppelganger from the film “Wallstreet“, Lord’s systemic power is merely a dream he projects, first metaphorically and then magically.

What Pedro Pascal gave us was something we rarely ever see in the superhero genre – a Latino villain that doesn’t lean heavily into racist stereotypes. When “Arrow” introduced season six antagonist Ricardo “The Dragon” Diaz (Kirk Acevedo), I genuinely became excited. Here was a Latino villain who wasn’t just a glorified gangbanger; he was a starving orphan who used his wits and mad martial arts skills to become a top-tier kingpin. Brushed off as a ‘second-rate drug dealer’ by law enforcement, Diaz often used being underestimated to his advantage. Sure, the drug dealer aspect of his character felt a bit racist, but there was genius sophistication to his villainy, like a reservoir Sun Tzu.

And then they romantically paired Diaz with fellow villain Black Siren… where he then proceeded to physically abuse her, at one point slamming her against a wall and choking her while she looked on in helpless terror. It was frustrating to watch, because “Arrow” took an otherwise interesting villain and demoted him to the role of ‘misogynistic cholo.’

What I loved about Max Lord was his villainy didn’t lean into racist stereotypes. While he does seduce Minerva into handing him the Dreamstone, he doesn’t merely discard her afterward. In fact, when Barbara playfully hints about her sexual encounter with Max to Diana, it genuinely seemed like she had a good time with him. And later on when she throws down with Wonder Woman to protect Max, he is quick to offer his gratitude and pledge his loyalty to her. His villainy isn’t wrapped up in sexist machismo, but something rarely talked about within LatinX culture (at least not in a pop culture setting). He’s every prominent Latino to ever change their name and put on a façade of Whiteness in order to be ‘more marketable.’

He’s like my grandma, who was literally beaten into aspirations of Whiteness throughout the many decades of her life.

But WW84 doesn’t just give Pascal an opportunity to be a compelling villain. Like all of Pascal’s roles there’s more to him than just his base nature, and the third act of the film proves it. While some of the plot drags at times, I felt that Patty Jenkins and Co. did something truly unique with the final confrontation. Rather than have Wonder Woman defeat Max Lord with her fists of fury, she did it with her voice of reason. As Max pitches his magical Ponzi scheme to the planet under the glow of a particle broadcaster, Diana recounts a lesson she learned in her youth; a scene depicted in the film’s opening credits.

When young Diana (Lilly Aspell) takes an unintended shortcut while competing in a great Amazonian tournament, she is stopped from completing the course by none other than General Antiope (Robin Wright). Diana sobs that she would have won had it not been for a stroke of bad luck, but Antiope reminds her that “No true hero is born from lies.”

Diana shares this wisdom with Max, informing him that you can’t have everything that you want, “only the truth, and that’s enough because the truth is beautiful.” Using her Lasso of Truth, Wonder Woman forces Max to confront his past trauma and face the harsh realities about himself. As Hans Zimmer’s haunting score “A Beautiful Lie” begins to play, Max suddenly realizes he’s been chasing a mirage of himself the entire time, and harming his son in the process.

Reconciling with his truth, Max rescinds his stolen power in order to save Alistair. Rushing to his boy, Max tearfully exclaims that Alistair will never have to wish for his love, adding that he hopes to make him proud of his father someday. With all the purity of an innocent child, Alistair replies “I don’t need you to make me proud. I already love you, daddy.” It became clear to me during this scene that Maxwell Lorenzano likely never experienced unconditional love until his son came into being. In the end, Wonder Woman was able to convince Max to stop living his sham existence and embrace the one authentic part of his life.

What makes it so frustrating to see White liberals talk about WW84’s lack of diversity is that many of them stayed silent when studios saturated the superhero market with overwhelmingly lily-White casts for decades, but only decided to speak up about inclusion now that a Latino star has seemingly stolen the show. When discussing inclusion, often times our representation can feel like an afterthought. It seems like White liberals pay little attention to LatinX visibility, unless it’s to vaguely criticize it. Pedro Pascal is hardly the only Latino icon to be White-washed by social media for the sake of outrage, and he undoubtedly won’t be the last. What’s frustrating is that the diversity discussion is something long overdue in Hollywood; it’s just rarely ever discussed in a healthy, equitable manner.

“Wonder Woman 1984″ has its flaws, but Pedro Pascal’s portrayal of a D-List villain wasn’t one of them. The veteran actor pours every ounce of manic energy into the role, and it’s obvious to anyone who’s lived the character’s life experiences who and what he’s supposed to represent. He’s someone who has suffered from systemic oppression, then went out of his way to pay it forward. He’s a sellout, but one who ultimately found his way again. Though I in no way claim to speak on behalf of all Mexican-Americans, conversations with many of my close LatinX friends made me realize I wasn’t alone in my feelings about Max Lord. With discord over the film causing flame-wars throughout social media, I sincerely wish that the film’s most ardent haters could at the very least appreciate the complex villainy of a genuinely interesting character of color.

“Wonder Woman 1984” is in select theaters now, and available to stream, on HBO Max.

![Representation Matters: Why I Loved Pedro Pascal As Max Lord [Opinion]](https://i0.wp.com/nerdbot.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/maxlord.2.jpg?fit=788%2C591&ssl=1)